9/19/2017

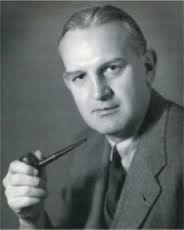

COMMODORE WALTER H. WHEELER, JR (1897-1977)

His friends called him Tiny, because he wasn’t. Walter Heber Wheeler, Jr. was born in NYC. His parents divorced and his mother later married Walter H. Bowes, an English immigrant who had sailed with her ex-husband. Bowes owned a Stamford company that manufactured machines used by the postal service to print cancellation information on mail. When he foresaw the need for a machine that would print postage in place of stamps, he met with inventor Arthur Pitney, who was perfecting such a machine. They established Pitney Bowes in 1920 and, though they shared the US Postal franchise with others, they provided their service so efficiently that they dominated the market. Despite their success, the co-founders did not get along, so Pitney resigned just four years later. Bowes was an entrepreneur and salesman, not a manager, and he hated to spend time at the office when he could be sailing or racing horses, so Pitney Bowes needed a general manager.

Walter Wheeler had been elected captain of Harvard’s football team just before he left to serve in World War I. He drove an ambulance for the French at Verdun and later became a US Navy officer on a submarine chaser. He had worked at Pitney Bowes for only a few years when his stepfather asked him to become what we would call Chief Operating Officer. Wheeler was promoted to President in 1938 and CEO a short-time later. Bowes sailed off with a lucrative consulting contract around 1940.

Wheeler stayed at the helm of Pitney Bowes for the next three decades. He believed in treating his employees fairly and having a workforce as diverse as the communities in which the business operated. He vigorously defended his people from bigotry, wherever they traveled, and was an outspoken opponent of McCarthyism, despite his company’s dependence on a Federal Government concession.

Wheeler’s lifelong yacht racing career put our Club on the map in that sport, and you can get a taste of it from the Cotton Blossom display in the southeast corner of the ballroom. He served as Commodore in 1933-34, and his advocacy during that decade is largely responsible for harbor dredging and the building of the breakwater in the early 1940s. He later encouraged the Club to thank the people of Stamford by keeping the harbor clean and doing all it could to make sailing on the Sound available to those who could not afford to be members. (SYC’s support of high school sailing and the Stamford Sailing Foundation are later responses to that vision.)

Perhaps Wheeler’s most important role in SYC’s evolution is the one that is least discussed. In early 1940, he was told that lending Cotton Blossom to a non-member friend (an esteemed lawyer and philanthropist) would be impossible because the friend was a Jew and, for that reason only, could not be allowed to use the Club’s launches. Wheeler, in a letter to Commodore Fownes, wrote: “Either I acquiesce to the unfair discrimination which prevents this, or I endeavor to do my part, small as it may be, towards creating a fairer situation, if not for him, for others like him. If this means putting myself in his position, it will be a salutary experience for me—and it would be for others.” Wheeler resigned his membership.

Fourteen years later, on the recommendation of Commodore Robinson, the Board resolved that no applicant for admission to SYC could be refused on the basis of race or religion. Commodore Wheeler was immediately informed and invited to return to the Club. He was formally readmitted at the Board’s next meeting. In 2008, Commodore Wheeler was remembered again when members attending the annual meeting added a comprehensive non-discrimination policy to the Club’s Constitution (Article X, Section 4).

Staff Commodore Christopher Hynes

Club Historian